Lifted Model Checking for Relational MDPs

An efficient formal verification framework for Safety in AI

Why model checking?

Probabilistic Model Checking aims at deciding whether a stochastic model satisfies a given probabilistic property. It provides rigorous guarantees about the model and allows for statements such as:

- The machine gives a warning before shutting down with a probability higher than 0.95.

- The emergency power supply, after giving a warning, continues to function for at least 10 more minutes with a probability higher than 0.9.

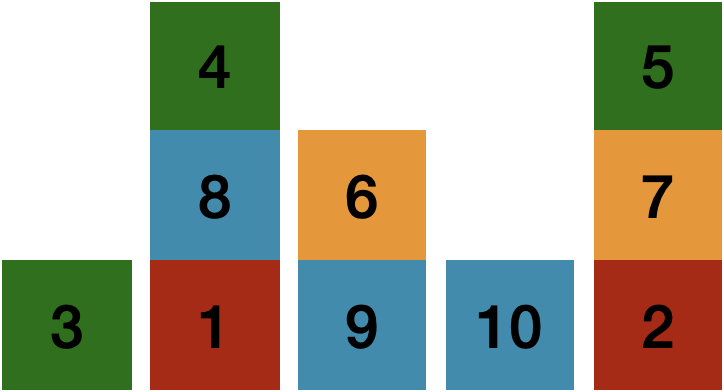

We illustrate Probabilistic Model Checking using a simple blocks world. Imagine there are a number of blocks numbered 1, 2, etc. Each block has one of four colors: green, red, blue, or yellow (e.g., a red block with ID 1 is expressed as “red(1)”). A block can be on top of another block (e.g., block 8 on top of block 1 is expressed as “on(8,1)”). A clear block (with no other block on top) is expressed as “cl(1)”. The following figure shows a configuration.

red(1), red(2), green(3), green(4), green(5),

yellow(6), yellow(7), blue(8), blue(9), blue(10),

on(4,8), on(8,1), on(6,9), on(5,7), on(7,2),

cl(3), cl(4), cl(6), cl(10), cl(5)

Question: How many possible configurations are there if we have 10 blocks as shown in Fig 1? Answer: Over 58 million configurations.

This is a surprisingly large number of configurations with only 10 blocks! In fact, blocks world is a well-known planning domain with NP-hard complexity. The number grows exponentially with the number of objects. To illustrate this, suppose there is only 1 red block. Then, we have exactly 1 configuration, i.e., red(1). If there are 2 red blocks, then we have 3 configurations:

s1 = cl(1), cl(2)

s2 = cl(1), on(1, 2)

s3 = cl(2), on(2, 1)

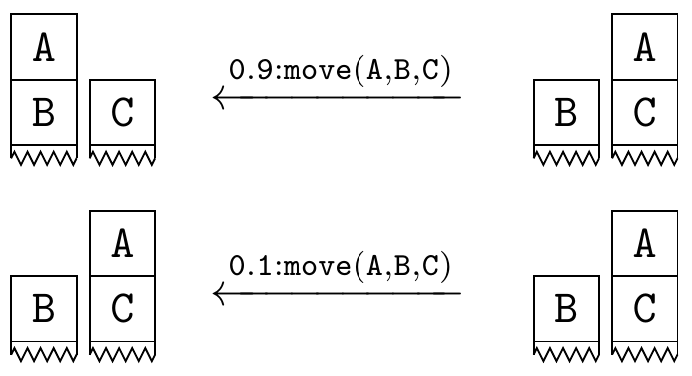

All these configurations are connected by actions. For example, we have a robot that can move around and arrange the blocks with a success probability of 0.9 (the robot fails to pick up a block with a probability of 0.1).

Model checking as a human

The model checking problem goes one step beyond counting the number of configurations and aims to find configurations that satisfy a given safety constraint. A model checker can answer questions such as:

Property to be checked: What are the configurations that can reach a goal configuration in which a red block is on another red block within 5 actions with a probability larger than 0.8?

This requires checking:

- Is the goal configuration reachable within 5 actions?

- If so, is the probability larger than 0.8?

If we have 10 blocks, we must apply the transition 5 times for all 58 million states, which would take a long time even with state-of-the-art model checkers. As human beings, we excel at abstracting problems and reasoning at a high level. The goal configuration is g = {on(X, Y), red(X), red(Y)}, meaning that some red block X is on some other red block Y. Here, X and Y are logical variables that represent arbitrary blocks.

It is trivial that {red(X), red(Y), cl(X), cl(Y)} is one action away from the goal by putting X on Y.

Similarly, {red(X), red(Y), cl(Z), cl(Y), on(Z, X)} is two actions away from the goal by moving Z away from X. Additionally, {red(X), red(Y), cl(Z), cl(Y), on(Z, Y)} is also two actions away from the goal by moving Z away from Y.

By following this reasoning, in order for the configuration in the above figure to satisfy the safety property, we must

- use 4 actions to move away all 4 blocks away from block 1 and 2

- then, move block 1 on block 2 or block 2 on block 1

And all five actions must succeed and the probability is 0.9^5 = 0.59 Therefore, the configuration in the figure does not satisfy the constraint.

Voilà! We have solved the problem exactly without enumerating all 58 million states by using lifting. Lifting allows us to reason at the first-order level (i.e., in terms of X and Y but not actual blocks) and think about a group of configurations as a whole. This is a core idea of PCTL-REBEL, the lifted model checker that we introduce in the paper. I refer the readers to the paper for more mathematical details and the algorithms if you have questions about:

- How exactly should the probability be computed, considering an action can fail?

- Can I check complex properties such as what configurations can reach configuration A, and then configuration B?

- What is the pseudocode of the algorithm?

- Is there a step-by-step demonstration of the algorithm?

- …

Results

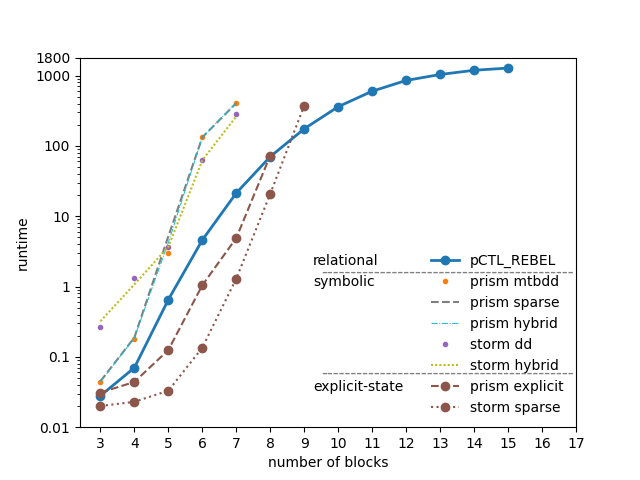

We compare PCTL-REBEL with the state-of-the-art model checkers PRISM and STORM. With a 30-minute time constraint, PCTL-REBEL can check 15 blocks, while STORM can check 9 blocks and PRISM can check 8 blocks. This is an improvement from 4.5 million to 65 trillion configurations.

Model checking for infinite models

When we have an unlimited number of blocks, the task of model checking becomes very difficult due to its NP-hard and undecidable nature.

The model checking problem is undecidable because an infinite number of blocks creates an infinitely large configuration, making it impossible to enumerate all configurations. It is NP-hard because it resembles the halting problem, where the system must halt when it finds a configuration that satisfies a given property, otherwise it continues to run indefinitely.

We overcome the decidability problem for a class of infinite systems by creating a finite representation that contains all necessary information about the underlying infinite system regarding a given property. This enables us to verify the system by examining the abstraction, which is equivalent to checking the infinite system.

We have employed lifting techniques and have demonstrated that PCTL-REBEL can be utilized with minor modifications for infinite models. The implementation is available online.